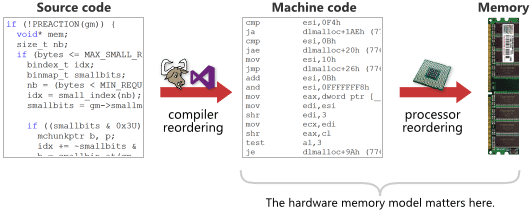

There are many types of memory reordering, and not all types of reordering occur equally often. It all depends on processor you’re targeting and/or the toolchain you’re using for development.

A memory model tells you, for a given processor or toolchain, exactly what types of memory reordering to expect at runtime relative to a given source code listing. Keep in mind that the effects of memory reordering can only be observed when lock-free programming techniques are used.

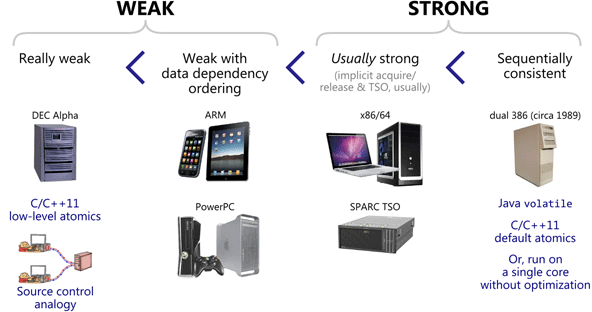

After studying memory models for a while – mostly by reading various online sources and verifying through experimentation – I’ve gone ahead and organized them into the following four categories. Below, each memory model makes all the guarantees of the ones to the left, plus some additional ones. I’ve drawn a clear line between weak memory models and strong ones, to capture the way most people appear to use these terms. Read on for my justification for doing so.

Each physical device pictured above represents a hardware memory model. A hardware memory model tells you what kind of memory ordering to expect at runtime relative to an assembly (or machine) code listing.

Every processor family has different habits when it comes to memory reordering, and those habits can only be observed in multicore or multiprocessor configurations. Given that multicore is now mainstream, it’s worth having some familiarity with them.

There are software memory models as well. Technically, once you’ve written (and debugged) portable lock-free code in C11, C++11 or Java, only the software memory model is supposed to matter. Nonetheless, a general understanding of hardware memory models may come in handy. It can help you explain unexpected behavior while debugging, and — perhaps just as importantly — appreciate how incorrect code may function correctly on a specific processor and toolchain out of luck.

Weak Memory Models

In the weakest memory model, it’s possible to experience all four types of memory reordering I described using a source control analogy in a previous post. Any load or store operation can effectively be reordered with any other load or store operation, as long as it would never modify the behavior of a single, isolated thread. In reality, the reordering may be due to either compiler reordering of instructions, or memory reordering on the processor itself.

In the weakest memory model, it’s possible to experience all four types of memory reordering I described using a source control analogy in a previous post. Any load or store operation can effectively be reordered with any other load or store operation, as long as it would never modify the behavior of a single, isolated thread. In reality, the reordering may be due to either compiler reordering of instructions, or memory reordering on the processor itself.

When a processor has a weak hardware memory model, we tend to say it’s weakly-ordered or that it has weak ordering. We may also say it has a relaxed memory model. The venerable DEC Alpha is everybody’s favorite example of a weakly-ordered processor. There’s really no mainstream processor with weaker ordering.

The C11 and C++11 programming languages expose a weak software memory model which was in many ways influenced by the Alpha. When using low-level atomic operations in these languages, it doesn’t matter if you’re actually targeting a strong processor family such as x86/64. As I demonstrated previously, you must still specify the correct memory ordering constraints, if only to prevent compiler reordering.

Weak With Data Dependency Ordering

Though the Alpha has become less relevant with time, we still have several modern CPU families which carry on in the same tradition of weak hardware ordering:

- ARM, which is currently found in hundreds of millions of smartphones and tablets, and is increasingly popular in multicore configurations.

- PowerPC, which the Xbox 360 in particular has already delivered to 70 million living rooms in a multicore configuration.

- Itanium, which Microsoft no longer supports in Windows, but which is still supported in Linux and found in HP servers.

These families have memory models which are, in various ways, almost as weak as the Alpha’s, except for one common detail of particular interest to programmers: they maintain data dependency ordering. What does that mean? It means that if you write A->B in C/C++, you are always guaranteed to load a value of B which is at least as new as the value of A. The Alpha doesn’t guarantee that. I won’t dwell on data dependency ordering too much here, except to mention that the Linux RCU mechanism relies on it heavily.

Strong Memory Models

Let’s look at hardware memory models first. What, exactly, is the difference between a strong one and a weak one? There is actually a little disagreement over this question, but my feeling is that in 80% of the cases, most people mean the same thing. Therefore, I’d like to propose the following definition:

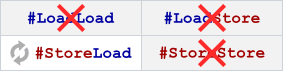

A strong hardware memory model is one in which every machine instruction comes implicitly with acquire and release semantics. As a result, when one CPU core performs a sequence of writes, every other CPU core sees those values change in the same order that they were written.

It’s not too hard to visualize. Just imagine a refinement of the source control analogy where all modifications are committed to shared memory in-order (no StoreStore reordering), pulled from shared memory in-order (no LoadLoad reordering), and instructions are always executed in-order (no LoadStore reordering). StoreLoad reordering, however, still remains possible.

Under the above definition, the x86/64 family of processors is usually strongly-ordered. There are certain cases in which some of x86/64’s strong ordering guarantees are lost, but for the most part, as application programmers, we can ignore those cases. It’s true that a x86/64 processor can execute instructions out-of-order, but that’s a hardware implementation detail – what matters is that it still keeps its memory interactions in-order, so in a multicore environment, we can still consider it strongly-ordered. Historically, there has also been a little confusion due to evolving specs.

Apparently SPARC processors, when running in TSO mode, are another example of a strong hardware ordering. TSO stands for “total store order”, which in a subtle way, is different from the definition I gave above. It means that there is always a single, global order of writes to shared memory from all cores. The x86/64 has this property too: See Volume 3, §8.2.3.6-8 of Intel’s x86/64 Architecture Specification for some examples. From what I can tell, the TSO property isn’t usually of direct interest to low-level lock-free programmers, but it is a step towards sequential consistency.

Sequential Consistency

In a sequentially consistent memory model, there is no memory reordering. It’s as if the entire program execution is reduced to a sequential interleaving of instructions from each thread. In particular, the result r1 = r2 = 0 from Memory Reordering Caught in the Act becomes impossible.

These days, you won’t easily find a modern multicore device which guarantees sequential consistency at the hardware level. However, it seems at least one sequentially consistent, dual-processor machine existed back in 1989: The 386-based Compaq SystemPro. According to Intel’s docs, the 386 wasn’t advanced enough to perform any memory reordering at runtime.

In any case, sequential consistency only really becomes interesting as a software memory model, when working in higher-level programming languages. In Java 5 and higher, you can declare shared variables as

In any case, sequential consistency only really becomes interesting as a software memory model, when working in higher-level programming languages. In Java 5 and higher, you can declare shared variables as volatile. In C++11, you can use the default ordering constraint, memory_order_seq_cst, when performing operations on atomic library types. If you do those things, the toolchain will restrict compiler reordering and emit CPU-specific instructions which act as the appropriate memory barrier types. In this way, a sequentially consistent memory model can be “emulated” even on weakly-ordered multicore devices. If you read Herlihy & Shavit’s The Art of Multiprocessor Programming, be aware that most of their examples assume a sequentially consistent software memory model.

Further Details

There are many other subtle details filling out the spectrum of memory models, but in my experience, they haven’t proved quite as interesting when writing lock-free code at the application level. There are things like control dependencies, causal consistency, and different memory types. Still, most discussions come back the four main categories I’ve outlined here.

If you really want to nitpick the fine details of processor memory models, and you enjoy eating formal logic for breakfast, you can check out the admirably detailed work done at the University of Cambridge. Paul McKenney has written an accessible overview of some of their work and its associated tools.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming