Atomic read-modify-write operations – or “RMWs” – are more sophisticated than atomic loads and stores. They let you read from a variable in shared memory and simultaneously write a different value in its place. In the C++11 atomic library, all of the following functions perform an RMW:

std::atomic<>::fetch_add() std::atomic<>::fetch_sub() std::atomic<>::fetch_and() std::atomic<>::fetch_or() std::atomic<>::fetch_xor() std::atomic<>::exchange() std::atomic<>::compare_exchange_strong() std::atomic<>::compare_exchange_weak()

fetch_add, for example, reads from a shared variable, adds another value to it, and writes the result back – all in one indivisible step. You can accomplish the same thing using a mutex, but a mutex-based version wouldn’t be lock-free. RMW operations, on the other hand, are designed to be lock-free. They’ll take advantage of lock-free CPU instructions whenever possible, such as ldrex/strex on ARMv7.

A novice programmer might look at the above list of functions and ask, “Why does C++11 offer so few RMW operations? Why is there an atomic fetch_add, but no atomic fetch_multiply, no fetch_divide and no fetch_shift_left?” There are two reasons:

- Because there is very little need for those RMW operations in practice. Try not to get the wrong impression of how RMWs are used. You can’t write safe multithreaded code by taking a single-threaded algorithm and turning each step into an RMW.

- Because if you do need those operations, you can easily implement them yourself. As the title says, you can do any kind of RMW operation!

Compare-and-Swap: The Mother of All RMWs

Out of all the available RMW operations in C++11, the only one that is absolutely essential is compare_exchange_weak. Every other RMW operation can be implemented using that one. It takes a minimum of two arguments:

shared.compare_exchange_weak(T& expected, T desired, ...);

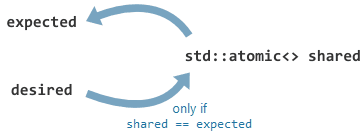

This function attempts to store the desired value to shared, but only if the current value of shared matches expected. It returns true if successful. If it fails, it loads the current value of shared back into expected, which despite its name, is an in/out parameter. This is called a compare-and-swap operation, and it all happens in one atomic, indivisible step.

So, suppose you really need an atomic fetch_multiply operation, though I can’t imagine why. Here’s one way to implement it:

uint32_t fetch_multiply(std::atomic<uint32_t>& shared, uint32_t multiplier)

{

uint32_t oldValue = shared.load();

while (!shared.compare_exchange_weak(oldValue, oldValue * multiplier))

{

}

return oldValue;

}

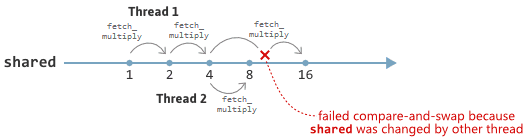

This is known as a compare-and-swap loop, or CAS loop. The function repeatedly tries to exchange oldValue with oldValue * multiplier until it succeeds. If no concurrent modifications happen in other threads, compare_exchange_weak will usually succeed on the first try. On the other hand, if shared is concurrently modified by another thread, it’s totally possible for its value to change between the call to load and the call to compare_exchange_weak, causing the compare-and-swap operation to fail. In that case, oldValue will be updated with the most recent value of shared, and the loop will try again.

The above implementation of fetch_multiply is both atomic and lock-free. It’s atomic even though the CAS loop may take an indeterminate number of tries, because when the loop finally does modify shared,shared successfully. That last statement hinges on the assumption that compare_exchange_weak actually compiles to lock-free machine code – more on that below. It also ignores the fact that compare_exchange_weak can fail spuriously on certain platforms, but that’s a rare event.

You Can Combine Several Steps Into One RMW

fetch_multiply just replaces the value of shared with a multiple of the same value. What if we want to perform a more elaborate kind of RMW? Can we still make the operation atomic and lock-free? Sure we can. To offer a somewhat convoluted example, here’s a function that loads a shared variable, decrements the value if odd, divides it in half if even, and stores the result back only if it’s greater than or equal to 10, all in a single atomic, lock-free operation:

uint32_t atomicDecrementOrHalveWithLimit(std::atomic<uint32_t>& shared)

{

uint32_t oldValue = shared.load();

uint32_t newValue;

do

{

if (oldValue % 2 == 1)

newValue = oldValue - 1;

else

newValue = oldValue / 2;

if (newValue < 10)

break;

}

while (!shared.compare_exchange_weak(oldValue, newValue));

return oldValue;

}

It’s the same idea as before: If compare_exchange_weak fails – usually due to a modification performed by another thread – oldValue is updated with a more recent value, and the loop tries again. If, during any attempt, we find that newValue is less than 10, the CAS loop terminates early, effectively turning the RMW operation into a no-op.

The point is that you can put anything inside the CAS loop. Think of the body of the CAS loop as a critical section. Normally, we protect a critical section using a mutex. With a CAS loop, we simply retry the entire transaction until it succeeds.

This is obviously a synthetic example. A more practical example can be seen in the AutoResetEvent class described in my earlier post about semaphores. It uses a CAS loop with multiple steps to atomically increment a shared variable up to a limit of 1.

You Can Combine Several Variables Into One RMW

So far, we’ve only looked at examples that perform an atomic operation on a single shared variable. What if we want to perform an atomic operation on multiple variables? Normally, we’d protect those variables using a mutex:

std::mutex mutex; uint32_t x; uint32_t y; void atomicFibonacciStep() { std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mutex); int t = y; y = x + y; x = t; }

This mutex-based approach is atomic, but obviously not lock-free. That may very well be good enough, but for the sake of illustration, let’s go ahead and convert it to a CAS loop just like the other examples. std::atomic<> is a template, so we can actually pack both shared variables into a struct and apply the same pattern as before:

struct Terms { uint32_t x; uint32_t y; }; std::atomic<Terms> terms; void atomicFibonacciStep() { Terms oldTerms = terms.load(); Terms newTerms; do { newTerms.x = oldTerms.y; newTerms.y = oldTerms.x + oldTerms.y; } while (!terms.compare_exchange_weak(oldTerms, newTerms)); }

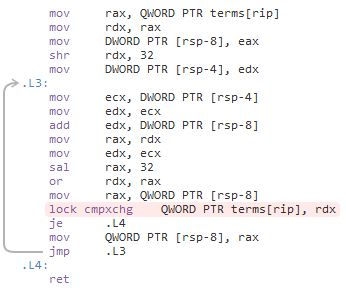

Is this operation lock-free? Now we’re venturing into dicey territory. As I wrote at the start, C++11 atomic operations are designed take advantage of lock-free CPU instructions “whenever possible” – admittedly a loose definition. In this case, we’ve wrapped std::atomic<> around a struct, Terms. Let’s see how GCC 4.9.2 compiles it for x64:

We got lucky. The compiler was clever enough to see that Terms fits inside a single 64-bit register, and implemented compare_exchange_weak using lock cmpxchg. The compiled code is lock-free.

This brings up an interesting point: In general, the C++11 standard does not guarantee that atomic operations will be lock-free. There are simply too many CPU architectures to support and too many ways to specialize the std::atomic<> template. You need to check with your compiler to make absolutely sure. In practice, though, it’s pretty safe to assume that atomic operations are lock-free when all of the following conditions are true:

- The compiler is a recent version MSVC, GCC or Clang.

- The target processor is x86, x64 or ARMv7 (and possibly others).

- The atomic type is

std::atomic<uint32_t>,std::atomic<uint64_t>orstd::atomic<T*>for some typeT.

As a personal preference, I like to hang my hat on that third point, and limit myself to specializations of the std::atomic<> template that use explicit integer or pointer types. The safe bitfield technique I described in the previous post gives us a convenient way to rewrite the above function using an explicit integer specialization, std::atomic<uint64_t>:

BEGIN_BITFIELD_TYPE(Terms, uint64_t)

ADD_BITFIELD_MEMBER(x, 0, 32)

ADD_BITFIELD_MEMBER(y, 32, 32)

END_BITFIELD_TYPE()

std::atomic<uint64_t> terms;

void atomicFibonacciStep()

{

Terms oldTerms = terms.load();

Terms newTerms;

do

{

newTerms.x = oldTerms.y;

newTerms.y = (uint32_t) (oldTerms.x + oldTerms.y);

}

while (!terms.compare_exchange_weak(oldTerms, newTerms));

}

Some real-world examples where we pack several values into an atomic bitfield include:

- Implementing tagged pointers as a workaround for the ABA problem.

- Implementing a lightweight read-write lock, which I touched upon briefly in a previous post.

In general, any time you have a small amount of data protected by a mutex, and you can pack that data entirely into a 32- or 64-bit integer type, you can always convert your mutex-based operations into lock-free RMW operations, no matter what those operations actually do! That’s the principle I exploited in my Semaphores are Surprisingly Versatile post, to implement a bunch of lightweight synchronization primitives.

Of course, this technique is not unique to the C++11 atomic library. I’m just using C++11 atomics because they’re quite widely available now, and compiler support is pretty good. You can implement a custom RMW operation using any library that exposes a compare-and-swap function, such as Win32, the Mach kernel API, the Linux kernel API, GCC atomic builtins or Mintomic. In the interest of brevity, I didn’t discuss memory ordering concerns in this post, but it’s critical to consider the guarantees made by your atomic library. In particular, if your custom RMW operation is intended to pass non-atomic information between threads, then at a minimum, you should ensure that there is the equivalent of a synchronizes-with relationship somewhere.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming