When writing lock-free code in C or C++, one must often take special care to enforce correct memory ordering. Otherwise, surprising things can happen.

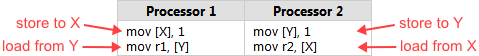

Intel lists several such surprises in Volume 3, §8.2.3 of their x86/64 Architecture Specification. Here’s one of the simplest examples. Suppose you have two integers X and Y somewhere in memory, both initially 0. Two processors, running in parallel, execute the following machine code:

Don’t be thrown off by the use of assembly language in this example. It’s really the best way to illustrate CPU ordering. Each processor stores 1 into one of the integer variables, then loads the other integer into a register. (r1 and r2 are just placeholder names for actual x86 registers, such as eax.)

Now, no matter which processor writes 1 to memory first, it’s natural to expect the other processor to read that value back, which means we should end up with either r1 = 1, r2 = 1, or perhaps both. But according to Intel’s specification, that won’t necessarily be the case. The specification says it’s legal for both r1 and r2 to equal 0 at the end of this example – a counterintuitive result, to say the least!

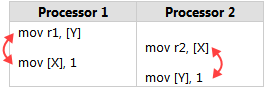

One way to understand this is that Intel x86/64 processors, like most processor families, are allowed to reorder the memory interactions of machine instructions according to certain rules, as long it never changes the execution of a single-threaded program. In particular, each processor is allowed to delay the effect of a store past any load from a different location. As a result, it might end up as though the instructions had executed in this order:

Let’s Make It Happen

It’s all well and good to be told this kind of thing might happen, but there’s nothing like seeing it with your own eyes. That’s why I’ve written a small sample program to show this type of reordering actually happening. You can download the source code here.

The sample comes in both a Win32 version and a POSIX version. It spawns two worker threads which repeat the above transaction indefinitely, while the main thread synchronizes their work and checks each result.

Here’s the source code for the first worker thread. X, Y, r1 and r2 are all globals, and POSIX semaphores are used to co-ordinate the beginning and end of each loop.

sem_t beginSema1; sem_t endSema; int X, Y; int r1, r2; void *thread1Func(void *param) { MersenneTwister random(1); // Initialize random number generator for (;;) // Loop indefinitely { sem_wait(&beginSema1); // Wait for signal from main thread while (random.integer() % 8 != 0) {} // Add a short, random delay // ----- THE TRANSACTION! ----- X = 1; asm volatile("" ::: "memory"); // Prevent compiler reordering r1 = Y; sem_post(&endSema); // Notify transaction complete } return NULL; // Never returns };

A short, random delay is added before each transaction in order to stagger the timing of the thread. Remember, there are two worker threads, and we’re trying to get their instructions to overlap. The random delay is achieved using the same MersenneTwister implementation I’ve used in previous posts, such as when measuring lock contention and when validating that the recursive Benaphore worked.

Don’t be spooked by the presence of the asm volatile line in the above code listing. This is just a directive telling the GCC compiler not to rearrange the store and the load when generating machine code, just in case it starts to get any funny ideas during optimization. We can verify this by checking the assembly code listing, as seen below. As expected, the store and the load occur in the desired order. The instruction after that writes the resulting register eax back to the global variable r1.

$ gcc -O2 -c -S -masm=intel ordering.cpp

$ cat ordering.s

...

mov DWORD PTR _X, 1

mov eax, DWORD PTR _Y

mov DWORD PTR _r1, eax

...

The main thread source code is shown below. It performs all the administrative work. After initialization, it loops indefinitely, resetting X and Y back to 0 before kicking off the worker threads on each iteration.

Pay particular attention to the way all writes to shared memory occur before sem_post, and all reads from shared memory occur after sem_wait. The same rules are followed in the worker threads when communicating with the main thread. Semaphores give us acquire and release semantics on every platform. That means we are guaranteed that the initial values of X = 0 and Y = 0 will propagate completely to the worker threads, and that the resulting values of r1 and r2 will propagate fully back here. In other words, the semaphores prevent memory reordering issues in the framework, allowing us to focus entirely on the experiment itself!

int main() { // Initialize the semaphores sem_init(&beginSema1, 0, 0); sem_init(&beginSema2, 0, 0); sem_init(&endSema, 0, 0); // Spawn the threads pthread_t thread1, thread2; pthread_create(&thread1, NULL, thread1Func, NULL); pthread_create(&thread2, NULL, thread2Func, NULL); // Repeat the experiment ad infinitum int detected = 0; for (int iterations = 1; ; iterations++) { // Reset X and Y X = 0; Y = 0; // Signal both threads sem_post(&beginSema1); sem_post(&beginSema2); // Wait for both threads sem_wait(&endSema); sem_wait(&endSema); // Check if there was a simultaneous reorder if (r1 == 0 && r2 == 0) { detected++; printf("%d reorders detected after %d iterations\n", detected, iterations); } } return 0; // Never returns }

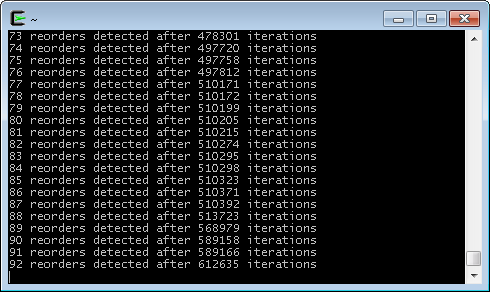

Finally, the moment of truth. Here’s some sample output while running in Cygwin on an Intel Xeon W3520.

And there you have it! During this run, a memory reordering was detected approximately once every 6600 iterations. When I tested in Ubuntu on a Core 2 Duo E6300, the occurrences were even more rare. One begins to appreciate how subtle timing bugs can creep undetected into lock-free code.

Now, suppose you wanted to eliminate those reorderings. There are at least two ways to do it. One way is to set thread affinities so that both worker threads run exclusively on the same CPU core. There’s no portable way to set affinities with Pthreads, but on Linux it can be accomplished as follows:

cpu_set_t cpus;

CPU_ZERO(&cpus);

CPU_SET(0, &cpus);

pthread_setaffinity_np(thread1, sizeof(cpu_set_t), &cpus);

pthread_setaffinity_np(thread2, sizeof(cpu_set_t), &cpus);

After this change, the reordering disappears. That’s because a single processor never sees its own operations out of order, even when threads are pre-empted and rescheduled at arbitrary times. Of course, by locking both threads to a single core, we’ve left the other cores unused.

On a related note, I compiled and ran this sample on Playstation 3, and no memory reordering was detected. This suggests (but doesn’t confirm) that the two hardware threads inside the PPU may effectively act as a single processor, with very fine-grained hardware scheduling.

Preventing It With a StoreLoad Barrier

Another way to prevent memory reordering in this sample is to introduce a CPU barrier between the two instructions. Here, we’d like to prevent the effective reordering of a store followed by a load. In common barrier parlance, we need a StoreLoad barrier.

On x86/64 processors, there is no specific instruction which acts only as a StoreLoad barrier, but there are several instructions which do that and more. The mfence instruction is a full memory barrier, which prevents memory reordering of any kind. In GCC, it can be implemented as follows:

for (;;) // Loop indefinitely { sem_wait(&beginSema1); // Wait for signal from main thread while (random.integer() % 8 != 0) {} // Add a short, random delay // ----- THE TRANSACTION! ----- X = 1; asm volatile("mfence" ::: "memory"); // Prevent memory reordering r1 = Y; sem_post(&endSema); // Notify transaction complete }

Again, you can verify its presence by looking at the assembly code listing.

...

mov DWORD PTR _X, 1

mfence

mov eax, DWORD PTR _Y

mov DWORD PTR _r1, eax

...

With this modification, the memory reordering disappears, and we’ve still allowed both threads to run on separate CPU cores.

Similar Instructions and Different Platforms

Interestingly, mfence isn’t the only instruction which acts as a full memory barrier on x86/64. On these processors, any locked instruction, such as xchg, also acts as a full memory barrier – provided you don’t use SSE instructions or write-combined memory, which this sample doesn’t. In fact, the Microsoft C++ compiler generates xchg when you use the MemoryBarrier intrinsic, at least in Visual Studio 2008.

The mfence instruction is specific to x86/64. If you want to make the code more portable, you could wrap this intrinsic in a preprocessor macro. The Linux kernel has wrapped it in a macro named smp_mb, along with related macros such as smp_rmb and smp_wmb, and provided alternate implementations on different architectures. For example, on PowerPC, smp_mb is implemented as sync.

All these different CPU families, each having unique instructions to enforce memory ordering, with each compiler exposing them through different instrincs, and each cross-platform project implementing its own portability layer… none of this helps simplify lock-free programming! This is partially why the C++11 atomic library standard was recently introduced. It’s an attempt to standardize things, and make it easier to write portable lock-free code.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming