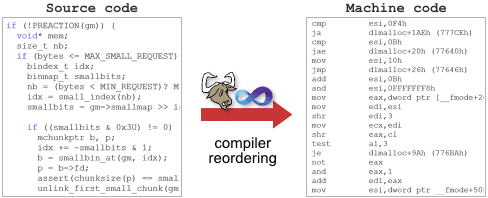

Between the time you type in some C/C++ source code and the time it executes on a CPU, the memory interactions of that code may be reordered according to certain rules. Changes to memory ordering are made both by the compiler (at compile time) and by the processor (at run time), all in the name of making your code run faster.

The cardinal rule of memory reordering, which is universally followed by compiler developers and CPU vendors, could be phrased as follows:

Thou shalt not modify the behavior of a single-threaded program.

As a result of this rule, memory reordering goes largely unnoticed by programmers writing single-threaded code. It often goes unnoticed in multithreaded programming, too, since mutexes, semaphores and events are all designed to prevent memory reordering around their call sites. It’s only when lock-free techniques are used – when memory is shared between threads without any kind of mutual exclusion – that the cat is finally out of the bag, and the effects of memory reordering can be plainly observed.

Mind you, it is possible to write lock-free code for multicore platforms without the hassles of memory reordering. As I mentioned in my introduction to lock-free programming, one can take advantage of sequentially consistent types, such as volatile variables in Java or C++11 atomics – possibly at the price of a little performance. I won’t go into detail about those here. In this post, I’ll focus on the impact of the compiler on memory ordering for regular, non-sequentially-consistent types.

Compiler Instruction Reordering

As you know, the job of a compiler is to convert human-readable source code into machine-readable code for the CPU. During this conversion, the compiler is free to take many liberties.

Once such liberty is the reordering of instructions – again, only in cases where single-threaded program behavior does not change. Such instruction reordering typically happens only when compiler optimizations are enabled. Consider the following function:

int A, B; void foo() { A = B + 1; B = 0; }

If we compile this function using GCC 4.6.1 without compiler optimization, it generates the following machine code, which we can view as an assembly listing using the -S option. The memory store to global variable B occurs right after the store to A, just as it does in the original source code.

$ gcc -S -masm=intel foo.c

$ cat foo.s

...

mov eax, DWORD PTR _B (redo this at home...)

add eax, 1

mov DWORD PTR _A, eax

mov DWORD PTR _B, 0

...

Compare that to the resulting assembly listing when optimizations are enabled using -O2:

$ gcc -O2 -S -masm=intel foo.c

$ cat foo.s

...

mov eax, DWORD PTR B

mov DWORD PTR B, 0

add eax, 1

mov DWORD PTR A, eax

...

This time, the compiler has chosen to exercise its liberties, and reordered the store to B before the store to A. And why shouldn’t it? The cardinal rule of memory ordering is not broken. A single-threaded program would never know the difference.

On the other hand, such compiler reorderings can cause problems when writing lock-free code. Here’s a commonly-cited example, where a shared flag is used to indicate that some other shared data has been published:

int Value; int IsPublished = 0; void sendValue(int x) { Value = x; IsPublished = 1; }

Imagine what would happen if the compiler reordered the store to IsPublished before the store to Value. Even on a single-processor system, we’d have a problem: a thread could very well be pre-empted by the operating system between the two stores, leaving other threads to believe that Value has been updated when in fact, it hasn’t.

Of course, the compiler might not reorder those operations, and the resulting machine code would work fine as a lock-free operation on any multicore CPU having a strong memory model, such as an x86/64 – or in a single-processor environment, any type of CPU at all. If that’s the case, we should consider ourselves lucky. Needless to say, it’s much better practice to recognize the possibility of memory reordering for shared variables, and to ensure that the correct ordering is enforced.

Explicit Compiler Barriers

The minimalist approach to preventing compiler reordering is by using a special directive known as a compiler barrier. I’ve already demonstrated compiler barriers in a previous post. The following is a full compiler barrier in GCC. In Microsoft Visual C++, _ReadWriteBarrier serves the same purpose.

int A, B; void foo() { A = B + 1; asm volatile("" ::: "memory"); B = 0; }

With this change, we can leave optimizations enabled, and the memory store instructions will remain in the desired order.

$ gcc -O2 -S -masm=intel foo.c

$ cat foo.s

...

mov eax, DWORD PTR _B

add eax, 1

mov DWORD PTR _A, eax

mov DWORD PTR _B, 0

...

Similarly, if we want to guarantee our sendMessage example works correctly, and we only care about single-processor systems, then at an absolute minimum, we must introduce compiler barriers here as well. Not only does the sending operation require a compiler barrier, to prevent the reordering of stores, but receiving side needs one between the loads as well.

#define COMPILER_BARRIER() asm volatile("" ::: "memory") int Value; int IsPublished = 0; void sendValue(int x) { Value = x; COMPILER_BARRIER(); // prevent reordering of stores IsPublished = 1; } int tryRecvValue() { if (IsPublished) { COMPILER_BARRIER(); // prevent reordering of loads return Value; } return -1; // or some other value to mean not yet received }

As I mentioned, compiler barriers are sufficient to prevent memory reordering on a single-processor system. But it’s 2012, and these days, multicore computing is the norm. If we want to ensure our interactions happen in the desired order in a multiprocessor environment, and on any CPU architecture, then a compiler barrier is not enough. We need either to issue a CPU fence instruction, or perform any operation which acts as a memory barrier at runtime. I’ll write more about those in the next post, Memory Barriers Are Like Source Control Operations.

The Linux kernel exposes several CPU fence instructions through preprocessor macros such as smb_rmb, and those macros are reduced to simple compiler barriers when compiling for a single-processor system.

Implied Compiler Barriers

There are other ways to prevent compiler reordering. Indeed, the CPU fence instructions I just mentioned act as compiler barriers, too. Here’s an example CPU fence instruction for PowerPC, defined as a macro in GCC:

#define RELEASE_FENCE() asm volatile("lwsync" ::: "memory")

Anywhere we place RELEASE_FENCE throughout our code, it will prevent certain kinds of processor reordering in addition to compiler reordering. For example, it can be used to make our sendValue function safe in a multiprocessor environment.

void sendValue(int x) { Value = x; RELEASE_FENCE(); IsPublished = 1; }

In the new C++11 (formerly known as C++0x) atomic library standard, every non-relaxed atomic operation acts as a compiler barrier as well.

int Value; std::atomic<int> IsPublished(0); void sendValue(int x) { Value = x; // <-- reordering is prevented here! IsPublished.store(1, std::memory_order_release); }

And as you might expect, every function containing a compiler barrier must act as a compiler barrier itself, even when the function is inlined. (However, Microsoft’s documentation suggests that may not have been the case in earlier versions of the Visual C++ compiler. Tsk, tsk!)

void doSomeStuff(Foo* foo) { foo->bar = 5; sendValue(123); // prevents reordering of neighboring assignments foo->bar2 = foo->bar; }

In fact, the majority of function calls act as compiler barriers, whether they contain their own compiler barrier or not. This excludes inline functions, functions declared with the pure attribute, and cases where link-time code generation is used. Other than those cases, a call to an external function is even stronger than a compiler barrier, since the compiler has no idea what the function’s side effects will be. It must forget any assumptions it made about memory that is potentially visible to that function.

When you think about it, this makes perfect sense. In the above code snippet, suppose our implementation of sendValue exists in an external library. How does the compiler know that sendValue doesn’t depend on the value of foo->bar? How does it know sendValue will not modify foo->bar in memory? It doesn’t. Therefore, to obey the cardinal rule of memory ordering, it must not reorder any memory operations around the external call to sendValue. Similarly, it must load a fresh value for foo->bar from memory after the call completes, rather than assuming it still equals 5, even with optimization enabled.

$ gcc -O2 -S -masm=intel dosomestuff.c

$ cat dosomestuff.s

...

mov ebx, DWORD PTR [esp+32]

mov DWORD PTR [ebx], 5 // Store 5 to foo->bar

mov DWORD PTR [esp], 123

call sendValue // Call sendValue

mov eax, DWORD PTR [ebx] // Load fresh value from foo->bar

mov DWORD PTR [ebx+4], eax

...

As you can see, there are many instances where compiler instruction reordering is prohibited, and even when the compiler must reload certain values from memory. I believe these hidden rules form a big part of the reason why people have long been saying that volatile data types in C are not usually necessary in correctly-written multithreaded code.

Out-Of-Thin-Air Stores

Think instruction reordering makes lock-free programming tricky? Before C++11 was standardized, there was technically no rule preventing the compiler from getting up to even worse tricks. In particular, compilers were free to introduce stores to shared memory in cases where there previously was none. Here’s a very simplified example, inspired by the examples provided in multiple articles by Hans Boehm.

int A, B; void foo() { if (A) B++; }

Though it’s rather unlikely in practice, nothing prevents a compiler from promoting B to a register before checking A, resulting in machine code equivalent to the following:

void foo() { register int r = B; // Promote B to a register before checking A. if (A) r++; B = r; // Surprise! A new memory store where there previously was none. }

Once again, the cardinal rule of memory ordering is still followed. A single-threaded application would be none the wiser. But in a multithreaded environment, we now have a function which can wipe out any changes made concurrently to B in other threads – even when A is 0. The original code didn’t do that. This type of obscure, technical non-impossibility is part of the reason why people have been saying that C++ doesn’t support threads, despite the fact that we’ve been happily writing multithreaded and lock-free code in C/C++ for decades.

I don’t know anyone who ever fell victim to such “out-of-thin-air” stores in practice. Maybe it’s just because for the type of lock-free code we tend to write, there aren’t a whole lot of optimization opportunities fitting this pattern. I suppose if I ever caught this type of compiler transformation happening, I would search for a way to wrestle the compiler into submission. If it’s happened to you, let me know in the comments.

In any case, the new C++11 standard explictly prohibits such behavior from the compiler in cases where it would introduce a data race. The wording can be found in and around §1.10.22 of the most recent C++11 working draft:

Compiler transformations that introduce assignments to a potentially shared memory location that would not be modified by the abstract machine are generally precluded by this standard.

Why Compiler Reordering?

As I mentioned at the start, the compiler modifies the order of memory interactions for the same reason that the processor does it – performance optimization. Such optimizations are a direct consequence of modern CPU complexity.

I may going out on a limb, but I somehow doubt that compilers did a whole lot of instruction reordering in the early 80’s, when CPUs had only a few hundred thousand transistors at most. I don’t think there would have been much point. But since then, Moore’s Law has provided CPU designers with about 10000 times the number of transistors to play with, and those transistors have been spent on tricks such as pipelining, memory prefetching, ILP and more recently, multicore. As a result of some of those features, we’ve seen architectures where the order of instructions in a program can make a significant difference in performance.

I may going out on a limb, but I somehow doubt that compilers did a whole lot of instruction reordering in the early 80’s, when CPUs had only a few hundred thousand transistors at most. I don’t think there would have been much point. But since then, Moore’s Law has provided CPU designers with about 10000 times the number of transistors to play with, and those transistors have been spent on tricks such as pipelining, memory prefetching, ILP and more recently, multicore. As a result of some of those features, we’ve seen architectures where the order of instructions in a program can make a significant difference in performance.

The first Intel Pentium released in 1993, with its so-called U and V-pipes, was the first processor where I really remember people talking about pipelining and the significance of instruction ordering. More recently, though, when I step through x86 disassembly in Visual Studio, I’m actually surprised how little instruction reordering there is. On the other hand, out of the times I’ve stepped through SPU disassembly on Playstation 3, I’ve found that the compiler really went to town. These are just anecdotal experiences; it may not reflect the experience of others, and certainly should not influence the way we enforce memory ordering in our lock-free code.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming