Happens-before is a modern computer science term which is instrumental in describing the software memory models behind C++11, Java, Go and even LLVM.

You’ll find a definition of the happens-before relation in the specifications of each of the above languages. Conveniently, the definitions given in those specifications are basically the same, though each specification has a different way of saying it. Roughly speaking, the common definition can be stated as follows:

Let A and B represent operations performed by a multithreaded process. If A happens-before B, then the memory effects of A effectively become visible to the thread performing B before B is performed.

When you consider the various ways in which memory reordering can complicate lock-free programming, the guarantee that A happens-before B is a desirable one. There are several ways to obtain this guarantee, differing slightly from one programming language to next – though obviously, all languages must rely on the same mechanisms at the processor level.

No matter which programming language you use, they all have one thing in common: If operations A and B are performed by the same thread, and A’s statement comes before B’s statement in program order, then A happens-before B. This is basically a formalization of the “cardinal rule of memory ordering” I mentioned in an earlier post.

int A, B; void foo() { // This store to A ... A = 5; // ... effectively becomes visible before the following loads. Duh! B = A * A; }

That’s not the only way to achieve a happens-before relation. The C++11 standard states that, among other methods, you also can achieve it between operations in different threads using acquire and release semantics. I’ll talk about that more in the next post about synchronizes-with.

I’m pretty sure that the name of this relation may lead to confusion for some. It’s worth clearing up right away: The happens-before relation, under the definition given above, is not the same as A actually happening before B! In particular,

- A happens-before B does not imply A happening before B.

- A happening before B does not imply A happens-before B.

These statements might appear paradoxical, but they’re not. I’ll try to explain them in the following sections. Remember, happens-before is a formal relation between operations, defined by a family of language specifications; it exists independently of the concept of time. This is different from what we usually mean when we say that “A happens before B”; referring the order, in time, of real-world events. Throughout this post, I’ve been careful to always hyphenate the former term happens-before, in order to distinguish it from the latter.

Happens-Before Does Not Imply Happening Before

Here’s an example of operations having a happens-before relationship without actually happening in that order. The following code performs (1) a store to A, followed by (2) a store to B. According to the rule of program ordering, (1) happens-before (2).

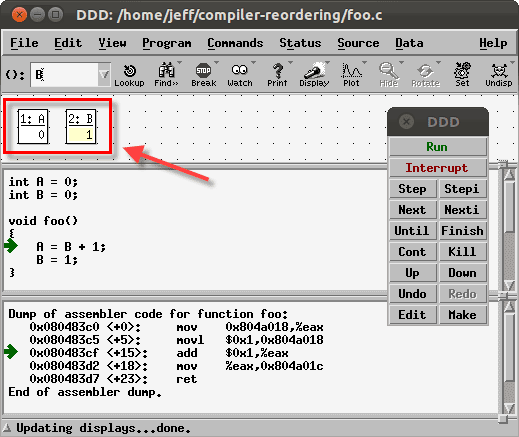

int A = 0; int B = 0; void foo() { A = B + 1; // (1) B = 1; // (2) }

However, if we compile this code with -O2 using GCC, the compiler performs some instruction reordering. As a result, when we step through the resulting code at the disassembly level in the debugger, we clearly see that after the second machine instruction, the store to B has completed, but the store to A has not. In other words, (1) doesn’t actually happen before (2)!

Has the happens-before relation been violated? Let’s see. According to the definition, the memory effects of (1) must effectively be visible before (2) is performed. In other words, the store to A must have a chance to influence the store to B.

In this case, though, the store to A doesn’t actually influence the store to B. (2) still behaves the same as it would have even if the effects of (1) had been visible, which is effectively the same as (1)’s effects being visible. Therefore, this doesn’t count as a violation of the happens-before rule. I’ll admit, this explanation is a bit dicey, but I’m fairly confident it’s consistent with the meaning of happen-before in all those language specifications.

Happening Before Does Not Imply Happens-Before

Here’s an example of operations which clearly happen in a specific order without constituting a happens-before relationship. In the following code, imagine that one thread calls publishMessage, while another thread calls consumeMessage. Since we’re manipulating shared variables concurrently, let’s keep it simple and assume that plain loads and stores of int are atomic. Because of program ordering, there is a happens-before relation between (1) and (2), and another happens-before relation between (3) and (4).

int isReady = 0; int answer = 0; void publishMessage() { answer = 42; // (1) isReady = 1; // (2) } void consumeMessage() { if (isReady) // (3) <-- Let's suppose this line reads 1 printf("%d\n", answer); // (4) }

Furthermore, let’s suppose that at runtime, the line marked (3) ends up reading 1, the value that was stored at line (2) in the other thread. In this case, we know that (2) must have happened before (3). But that doesn’t mean there is a happens-before relationship between (2) and (3)!

The happens-before relationship only exists where the language standards say it exists. And since these are plain loads and stores, the C++11 standard has no rule which introduces a happens-before relation between (2) and (3), even when (3) reads the value written by (2).

Furthermore, because there is no happens-before relation between (2) and (3), there is no happens-before relation between (1) and (4), either. Therefore, the memory interactions of (1) and (4) can be reordered, either due to compiler instruction reordering or memory reordering on the processor itself, such that (4) ends up printing “0”, even though (3) reads 1.

This post hasn’t really shown anything new. We already knew that memory interactions can be reordered when executing lock-free code. We’ve simply examined a term used in C++11, Java, Go and LLVM to formally specify the cases when memory reordering can be observed in those languages. Even Mintomic, a library I published several weeks ago, relies on the guarantees of happens-before, since it mimics the behavior of specific C++11 atomic library functions.

I believe the ambiguity that exists between the happens-before relation and the actual order of operations is part of what makes low-level lock-free programming so tricky. If nothing else, this post should have demonstrated that happens-before is a useful guarantee which doesn’t come cheaply between threads. I’ll expand on that further in the next post.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming