Raymond Chen defined acquire and release semantics as follows, back in 2008:

An operation with acquire semantics is one which does not permit subsequent memory operations to be advanced before it. Conversely, an operation with release semantics is one which does not permit preceding memory operations to be delayed past it.

Raymond’s definition applies perfectly well to Win32 functions like InterlockedIncrementRelease, which he was writing about at the time. It also applies perfectly well to atomic operations in C++11, such as store(1, std::memory_order_release).

It’s perhaps surprising, then, that this definition does not apply to standalone acquire and release fences in C++11! Those are a whole other ball of wax.

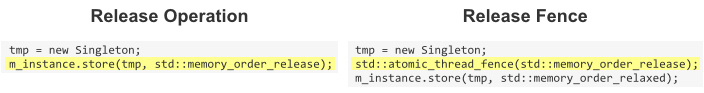

To see what I mean, consider the following two code listings. They’re both taken from my post about the double-checked locking pattern in C++11. The code on the left performs a release operation directly on m_instance, while the code on the right uses a release fence instead.

In both cases, the purpose is the same: to prevent other threads from observing the store to m_instance before any stores performed inside the Singleton constructor.

Now, what if Raymond’s definition of release semantics did apply to the release fence on the right? That would only mean that preceding memory operations are prevented from being reordered past the fence. But that guarantee, alone, is not enough. There would still be nothing to prevent the relaxed atomic store to m_instance, on the very next line, from being reordered before the fence – and even before the stores performed by the Singleton constructor – defeating the whole purpose of the fence in the first place.

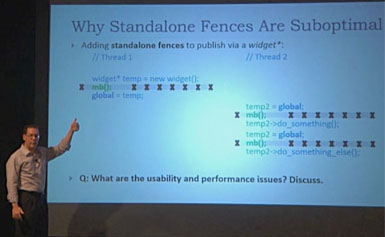

This misconception is very common. Herb Sutter himself makes this mistake at 1:10:35 in part 1 of his (otherwise superb) atomic<> Weapons talk, even going so far as to say that release makes no sense on a standalone fence.

“If this memory barrier were just one way – for instance, the memory barrier itself was a release… the write to global = temp can skip right over, and then all the code’s together again. Now the fox in the henhouse, and mayhem ensues.”

Fortunately, that’s not how C++11 release fences work. A release fence actually prevents all preceding memory operations from being reordered past subsequent writes. To his credit, Herb has acknowledged the error in a comment here.

In C++11, a Release Fence Is Not Considered a “Release Operation”

I think that the above misconception stems from some confusion about what is a “release operation” in C++11 and what isn’t. You might reasonably expect a release fence to be considered a “release operation”, but if you comb through the C++11 standard, you’ll find that it’s actually very careful not to call it that.

In the language of C++11, only a store can be a release operation, and only a load can be an acquire operation. (See §29.3.1 of working draft N3337.) A memory fence is neither a load nor a store, so obviously, it can’t be an acquire or release operation. Furthermore, if we accept that acquire and release semantics apply only to acquire and release operations, it’s clear that Raymond Chen’s definition does not apply to acquire and release fences. In my own post about acquire and release semantics, I was careful to specify the kind of operations on which they can apply.

Nor Can a Release Operation Take the Place of a Release Fence

It goes the other way, too. The two code listings near the start of this post both do a fine job of implementing DCLP, but they are not equivalent to each other. While the code on the right achieves all the effects of the code on the left, the reverse is not true: Technically, the code on the left does not achieve all the effects of the code on the right. The difference is quite subtle.

The release operation on the left, m_instance.store(tmp, std::memory_order_release), actually places fewer memory ordering constraints on neighboring operations than the release fence on the right. A release operation (such as the one on the left) only needs to prevent preceding memory operations from being reordered past itself, but a release fence (such as the one on the right) must prevent preceding memory operations from being reordered past all subsequent writes. Because of this difference, a release operation can never take the place of a release fence.

It’s easy to see why not. Consider what happens when we take the code listing on the right, and replace the release fence with a release operation on a separate atomic variable, g_dummy:

Singleton* tmp = new Singleton; g_dummy.store(0, std::memory_order_release); m_instance.store(tmp, std::memory_order_relaxed);

This time, we really do have the problem that Herb Sutter was worried about: The store to m_instance is now free to be reordered before the store to g_dummy, and possibly before any stores performed by the Singleton constructor. The fox is in the henhouse, and mayhem ensues!

(Interesting side note: An early draft of the C++11 standard, N2588, dating back to 2008, actually tried to define memory fences in a manner similar to this example. There was no standalone atomic_thread_fence function in that draft; there was only a member function on atomic objects, fence. For convenience, the draft included a global_fence_compatibility object, similar to the g_dummy object used here. A paper by Peter Dimov revealed some shortcomings in this design. As a result, the C++11 standard committee ditched the approach in favor of the standalone fence function we have today.)

Now That We’ve Cleared That Up…

Standalone memory fences are considered difficult to use, and I think part of the reason is because very few people even use the C++11 atomic library – let alone this part of it. As a result, misconceptions tend to go unnoticed more easily.

This particular misconception has bugged me for a while. Part of that is because earlier this year, I released an open source library called Mintomic. The only way to enforce memory ordering in Mintomic is by using standalone fences that are equivalent to those in C++11. I’d rather not have people think they don’t work!

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming