Python’s with statement was first introduced five years ago, in Python 2.5. It’s handy when you have two related operations which you’d like to execute as a pair, with a block of code in between. The classic example is opening a file, manipulating the file, then closing it:

with open('output.txt', 'w') as f: f.write('Hi there!')

The above with statement will automatically close the file after the nested block of code. (Continue reading to see exactly how the close occurs.) The advantage of using a with statement is that it is guaranteed to close the file no matter how the nested block exits. If an exception occurs before the end of the block, it will close the file before the exception is caught by an outer exception handler. If the nested block were to contain a return statement, or a continue or break statement, the with statement would automatically close the file in those cases, too.

Here’s another example. The pycairo drawing library contains a Context class which exposes a save method, to push the current drawing state on an internal stack, and a restore method, to restore the drawing state from the stack. These two functions are always called in a pair, with some code in between.

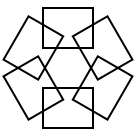

This code sample uses a Context object (“cairo context”) to draw six rectangles, each with a different rotation. Each call to rotate is actually combined with the current transformation, so we use a pair of calls to save and restore to preserve the drawing state on each iteration of the loop. This prevents the rotations from combining with each other:

cr.translate(68, 68) for i in xrange(6): cr.save() cr.rotate(2 * math.pi * i / 6) cr.rectangle(-25, -60, 50, 40) cr.stroke() cr.restore()

That’s a fairly simple example, but for larger scripts, it can become cumbersome to keep track of which save goes with which restore, and to keep them correctly matched. The with statement can help tidy things up a bit.

By themselves, pycairo’s save and restore methods do not support the with statement, so we’ll have to add the support on our own. There are two ways to support the with statement: by implementing a context manager class, or by writing a generator function. I’ll demonstrate both approaches.

Implementing the Context Manager as a Class

Here’s the first approach. To implement a context manager, we define a class containing an __enter__ and __exit__ method. The class below accepts a cairo context, cr, in its constructor:

class Saved(): def __init__(self, cr): self.cr = cr def __enter__(self): self.cr.save() return self.cr def __exit__(self, type, value, traceback): self.cr.restore()

Thanks to those two methods, it’s valid to instantiate a Saved object and use it in a with statement. The Saved object is considered to be the context manager.

cr.translate(68, 68) for i in xrange(6): with Saved(cr): cr.rotate(2 * math.pi * i / 6) cr.rectangle(-25, -60, 50, 40) cr.stroke()

Here are the exact steps taken by the Python interpreter when it reaches the with statement:

- The

withstatement stores theSavedobject in a temporary, hidden variable, since it’ll be needed later. (Actually, it only stores the bound__exit__method, but that’s a detail.) - The

withstatement calls__enter__on theSavedobject, giving the context manager a chance to do its job. - The

__enter__method callssaveon the cairo context. - The

__enter__method returns the cairo context, but as you can see, we have not specified the optional"as" targetpart of thewithstatement. Therefore, the return value is not saved anywhere. We don’t need it; we know it’s the same cairo context that we passed in. - The nested block of code is executed. It sets up the rotation and draws a rectangle.

- At the end of the nested block, the

withstatement calls theSavedobject’s__exit__method, passing the arguments(None, None, None)to indicate that no exception occured. - The

__exit__method callsrestoreon the cairo context.

Once we understand what the Python interpreter is doing, we can make better sense of the example at the beginning of this blog post, where we opened a file in the with statement: File objects expose their own __enter__ and __exit__ methods, and can therefore act as their own context managers. Specifically, the __exit__ method closes the file.

Exception Handling

Returning to the drawing example, what happens if an exception occurs within the nested code block? For example, suppose we mistakenly passed the wrong number of arguments to the rectangle call. In that case, the steps taken by the Python interpreter would be:

- The

rectanglemethod raises aTypeErrorexception: “Context.rectangle() takes exactly 4 arguments.” - The

withstatement catches this exception. - The

withstatement calls__exit__on theSavedobject. It passes information about the exception in three arguments: (type, value, traceback) – the same values you’d get by callingsys.exc_info. This tells the__exit__method everything it could possibly need to know about the exception that occurred. - In this case, our

__exit__method doesn’t particularly care. It callsrestoreon the cairo context anyway, and returnsNone. (In Python, when noreturnstatement is specified, the function actually returnsNone.) - The

withstatement checks to see whether this return value is true. Since it isn’t, thewithstatement re-raises theTypeErrorexception to be handled by someone else.

In this manner, we can guarantee that restore will always be called on the cairo context, whether an exception occurs or not.

Implementing the Context Manager as a Generator

That brings us to the second approach for supporting the with statement. Instead of implementing a class for the context manager, we can write a generator function. Here’s a simplified example of such a generator function. Let me point out right away that this example is incomplete, since it does not handle exceptions very well. Read on for more details:

from contextlib import contextmanager @contextmanager def saved(cr): cr.save() yield cr cr.restore()

There is a certain charm to writing a generator like this one. At first glance, it appears simpler than the previous approach: A single function takes the place of an entire class definition. But don’t be fooled! This approach involves many more steps, and a lot more complexity than the previous approach. It took me several reads of PEP 343 – which is more of a historical document than a reference – before I could claim to understand it completely. It requires familiarity with Python decorators, generators, iterators and functions-returning-functions, in addition to the object-oriented programming and exception handling we’ve already seen.

To make this generator work, two entities from contextlib, a standard Python module, are required: the contextmanager function, and an internal class named GeneratorContextManager. The source code, contextlib.py, is a bit hairy, but at least it’s short. I’ll simply describe what happens, and you are free to refer to the source code, and any other supplementary materials, as needed.

Let’s start with the generator itself. Here’s what happens when the above code snippet runs:

- The Python interpreter recognizes the

yieldstatement in the middle of the function definition. As a result, thedefstatement does not create a normal function; it creates a generator function. - Because of the presence of the

@contextmanagerdecorator,contextmanageris called with the generator function as its argument. - The

contextmanagerfunction returns a “factory” function, which createsGeneratorContextManagerobjects wrapped around the provided generator. (line 83 ofcontextlib.py) - Finally, the factory function is assigned to

saved. From this point on, when we callsaved, we’ll actually be calling the factory function.

Equipped with all that good stuff, we can now write:

for i in xrange(6): with saved(cr): cr.rotate(2 * math.pi * i / 6) cr.rectangle(-25, -60, 50, 40) cr.stroke()

Here are all the steps taken by the Python interpreter when it reaches the with statement.

- The

withstatement callssaved, which of course, calls the factory function, passingcr, a cairo context, as its only argument. - The factory function passes the cairo context to our generator function, creating a generator.

- The generator is passed to the constructor of

GeneratorContextManager, an internal class which will act as our context manager. - The

withstatement saves theGeneratorContextManagerobject in a temporary hidden variable. (Actually, it only stores the bound__exit__method, but that’s a detail.) - The

withstatement calls__enter__on theGeneratorContextManagerobject. __enter__callsnexton the generator.- Our generator function – the block of code we defined under

def saved(cr)– runs up until theyieldstatement. This callssaveon the cairo context. - The

yieldstatement yields the cairo context, which becomes the return value for the call tonexton the iterator. - The

__enter__method returns the cairo context, but as you can see, we have not specified the optional"as" targetpart of thewithstatement. Therefore, the return value is not saved anywhere. We don’t need it; we know it’s the same cairo context that we passed in. - The nested code block is executed. It sets up the rotation and draws a rectangle.

- At the end of the nested block, the

withstatement calls the__exit__method on theGeneratorContextManagerobject, passing the arguments(None, None, None)to indicate that no exception occured. - The

__exit__method callsnexton the iterator (expecting aStopIterationexception). - Our generator resumes execution after the

yieldstatement. This callsrestoreon the cairo context. - The generator returns, raising a

StopIterationexception (as expected). - The

__exit__method catches theStopIterationexception, and returns normally.

And that’s it! We’ve successfully used this generator function as a with statement context manager. In this example, it helped that no exceptions occured. To correctly deal with exceptions, we’ll have to improve the generator function a little bit.

Exception Handling

Now, what happens if an exception occurs within the nested block while using this approach? Again, let’s suppose we’ve mistakenly passed the wrong number of arguments to the rectangle call. Here’s what would happen:

- The

rectanglemethod raises aTypeErrorexception: “Context.rectangle() takes exactly 4 arguments.” - The

withstatement catches this exception. - The

withstatement calls__exit__on theGeneratorContextManagerobject. It passes information about the exception in three arguments: (type, value, traceback). __exit__callsthrowon the iterator, passing the same three arguments.- The

TypeErrorexception is raised in the context of our generator function, on the line containing theyieldstatement.

Uh oh! At this point, our current generator function has a problem: restore will not be called on the cairo context. An exception has been raised on the line containing the yield statement, so the rest of the generator function will not be executed. We need to make the generator more robust, by inserting a try/finally block around the yield:

@contextmanager def saved(cr): cr.save() try: yield cr finally: cr.restore()

Continuing where we left off:

- Inside our generator, the

finallyblock executes. This callsrestoreon the cairo context. - The

TypeErrorexception went unhandled by the generator, so it is re-raised in the__exit__method, on the line containing the call tothrowon the iterator. (line 35 ofcontextlib.py) - The

TypeErrorexception is caught by__exit__. __exit__sees that the exception caught is the same exception that was passed in, and as a result, returnsNone.- The

withstatement checks to see whether this return value is true. Since it isn’t, thewithstatement re-raises theTypeErrorexception, to be handled by someone else.

Thus concludes our journey through the Python with statement. If, like me, you’ve had a hard time understanding this statement completely – especially if you were attracted to the generator form of writing context managers – don’t feel bad. It’s complicated! It cleverly ties together several of Python’s language features, many of which were themselves introduced fairly recently in Python’s history. If any Pythonistas out there spot an error or oversight in the above explanation, please let me know in the comments.

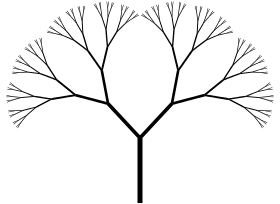

Drawing a Fractal Tree

For those of you who have endured the entire blog post up to this point, here’s a small bonus script. It uses our newly minted cairo context manager to recursively draw a fractal tree.

import cairo from contextlib import contextmanager @contextmanager def saved(cr): cr.save() try: yield cr finally: cr.restore() def Tree(angle): cr.move_to(0, 0) cr.translate(0, -65) cr.line_to(0, 0) cr.stroke() cr.scale(0.72, 0.72) if angle > 0.12: for a in [-angle, angle]: with saved(cr): cr.rotate(a) Tree(angle * 0.75) surf = cairo.ImageSurface(cairo.FORMAT_ARGB32, 280, 204) cr = cairo.Context(surf) cr.translate(140, 203) cr.set_line_width(5) Tree(0.75) surf.write_to_png('fractal-tree.png')

For yet another example of with statement usage in Python, see Timing Your Code Using Python’s “with” Statement.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming